Jonah and the Whale

Dive Travel Magazine Fall, 1997

by Catherine Holloway

Rugby

and religion reign supreme down here. At least, that's in the places where

following football is not officially classed as worship already. I'm talking

about the much romanticised South Pacific islands of Fiji and Tonga and

Rugby is the particular brand of football played so proudly in these parts.

This is a where every home in even the most remote villages displays a

poster of the local "footie legend", Jonah Lomu, the way a picture of the

Queen of England once adorned every mantelpiece in the colonies. The Pope?

Well, he rarely rates a mention nowadays.

Rugby

and religion reign supreme down here. At least, that's in the places where

following football is not officially classed as worship already. I'm talking

about the much romanticised South Pacific islands of Fiji and Tonga and

Rugby is the particular brand of football played so proudly in these parts.

This is a where every home in even the most remote villages displays a

poster of the local "footie legend", Jonah Lomu, the way a picture of the

Queen of England once adorned every mantelpiece in the colonies. The Pope?

Well, he rarely rates a mention nowadays.

Merely

hours before the year's crucial Rugby match between Fiji and Tonga, I ponder

my precarious position. I'm on board NAI'A, Fiji's luxury live-aboard

diving vessel, which boasts a formidable Fijian crew. But in our wide search

for humpback whales, we've anchored directly off a village in a region

of Tonga famous for its sizeable young men. Now, witnessing these islanders

play Rugby immediately dispels any travel brochure theory about tropical

folk being a gentle, languid, peace-loving bunch. These are people totally

in touch with their warrior heritage. All I can do is thank God the missionaries

triumphed over cannibalism.

Merely

hours before the year's crucial Rugby match between Fiji and Tonga, I ponder

my precarious position. I'm on board NAI'A, Fiji's luxury live-aboard

diving vessel, which boasts a formidable Fijian crew. But in our wide search

for humpback whales, we've anchored directly off a village in a region

of Tonga famous for its sizeable young men. Now, witnessing these islanders

play Rugby immediately dispels any travel brochure theory about tropical

folk being a gentle, languid, peace-loving bunch. These are people totally

in touch with their warrior heritage. All I can do is thank God the missionaries

triumphed over cannibalism.

Water both links and separates the neighbouring

nations of Fiji and Tonga. The exiled and adventurous risked all migrating

on these waters. Wars were fought, skills and materials were traded and

sustenance was harvested from the sea between them. Little has changed.

Sprayed alongside each other in the richest corner of the Pacific Ocean,

their many islands are as similar to one another as they are alien - historically,

geographically and culturally. But, nowhere are these inconsistencies and

ironies more obvious than below the water's surface.

Picture Nomuka'iki, a tiny coral atoll

and prison island in Tonga. One man guards one prisoner - not because he

is the country's only criminal but because the prison transport ship lays

wrecked and rusting on the reef just metres from the shore. Anchored here

for the evening is Adix, a lavish 216-foot three-masted schooner

whose anonymous philanthropic owners have spared no expense circumnavigating

the globe. The English hostess steals ashore after dusk with eggs, milk,

bread and a frozen rabbit for the prisoner. He's probably never seen a

rabbit before, let alone barbecued one. The scene seems bizarre yet completely

familiar. It reminds me of an old island proverb: "The coral waxes, the

palm grows, but man departs."

Europeans

had relatively little impact on these resilient and resourceful people.

The skill with which Fijians and Tongans have adapted to modern life is

perhaps less impressive than their commitment to the old ways. Fiji largely

escaped attention from explorers lusting for an undiscovered Australia

and it's hoped-for mineral wealth. The widely rumoured Fijian capacity

for violence and taste for flesh kept others at bay. Tonga is one of the

few nations never to be ruled by a Western power, unless you count the

enormous missionary influence, and operates even now as a Polynesian Kingdom.

Their long isolation has served them well - culturally that is. In both

countries, ancient ceremony and custom are still highly respected and practiced

routinely. And communal subsistence village life continues for the bulk

of the population outside the main towns. Most villages are still today

accessed by water. Shelter, flooring and clothing is still made from dried

and woven plants. Meals consist of fish still caught from carved wooden

canoes and vegetables grown by women toiling by hand in small "gardens".

Men still gather around the "grog" bowl nightly to talk and drink kava

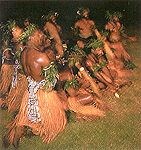

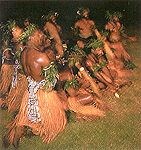

and women still perform formal dance and song rituals to mark significant

occasions. For all the development, progress, education and industry inflicted

on these islands, the people remain characteristically relaxed and inclined

to postpone any vigorous or demanding task - a tropical tendency called

"malua". Don't mistake this complacent manner for unfriendliness. It just

takes less valuable energy to nod subtly and raise an eyebrow than to wave

and shout hello.

Europeans

had relatively little impact on these resilient and resourceful people.

The skill with which Fijians and Tongans have adapted to modern life is

perhaps less impressive than their commitment to the old ways. Fiji largely

escaped attention from explorers lusting for an undiscovered Australia

and it's hoped-for mineral wealth. The widely rumoured Fijian capacity

for violence and taste for flesh kept others at bay. Tonga is one of the

few nations never to be ruled by a Western power, unless you count the

enormous missionary influence, and operates even now as a Polynesian Kingdom.

Their long isolation has served them well - culturally that is. In both

countries, ancient ceremony and custom are still highly respected and practiced

routinely. And communal subsistence village life continues for the bulk

of the population outside the main towns. Most villages are still today

accessed by water. Shelter, flooring and clothing is still made from dried

and woven plants. Meals consist of fish still caught from carved wooden

canoes and vegetables grown by women toiling by hand in small "gardens".

Men still gather around the "grog" bowl nightly to talk and drink kava

and women still perform formal dance and song rituals to mark significant

occasions. For all the development, progress, education and industry inflicted

on these islands, the people remain characteristically relaxed and inclined

to postpone any vigorous or demanding task - a tropical tendency called

"malua". Don't mistake this complacent manner for unfriendliness. It just

takes less valuable energy to nod subtly and raise an eyebrow than to wave

and shout hello.

But

how wrong it is to assume all South Pacific islands are the same! Fiji

and Tonga are worlds apart. Fijians are mostly Melanesian (recognized as

darker with coarse tightly curled hair) while Tongans are unmistakably

Polynesian (fairer and taller with straight hair). Fiji, in fact, was a

migratory frontier with Melanesians streaming from the west and Polynesians

from the east. Modern Fijians are a complex mix of Melanesian and Polynesian

strains. Warring Fijians crafted vicious weapons and built strongholds

in mountain crags and mangrove swamps while wandering Tongans developed

keen sailing skills and conquered distant coral atolls throughout the Pacific

to form the triangle of Polynesia (meaning many islands) within Hawaii,

Easter Island and New Zealand. Fiji's hardwood forests provided huge trees

for the great double canoes the Fijians became famous for building. These

canoes increased trading and communication with Tonga and, ironically,

later carried the waves of Tongan warriors who won control of much of eastern

Fiji. Feared and revered, Tongan warriors turned into sharks to cross the

seas and then became human again to fight on land - as legend has it.

But

how wrong it is to assume all South Pacific islands are the same! Fiji

and Tonga are worlds apart. Fijians are mostly Melanesian (recognized as

darker with coarse tightly curled hair) while Tongans are unmistakably

Polynesian (fairer and taller with straight hair). Fiji, in fact, was a

migratory frontier with Melanesians streaming from the west and Polynesians

from the east. Modern Fijians are a complex mix of Melanesian and Polynesian

strains. Warring Fijians crafted vicious weapons and built strongholds

in mountain crags and mangrove swamps while wandering Tongans developed

keen sailing skills and conquered distant coral atolls throughout the Pacific

to form the triangle of Polynesia (meaning many islands) within Hawaii,

Easter Island and New Zealand. Fiji's hardwood forests provided huge trees

for the great double canoes the Fijians became famous for building. These

canoes increased trading and communication with Tonga and, ironically,

later carried the waves of Tongan warriors who won control of much of eastern

Fiji. Feared and revered, Tongan warriors turned into sharks to cross the

seas and then became human again to fight on land - as legend has it.

Today,

Fiji sits on the main Pacific sea and air route and, thanks to sugar and

tourism, is, economically, the region's strongest and most developed nation.

Yet its people continue to value their heritage and traditions faithfully

in daily life. NAI'A's chef, Manasa, comes from Ra, a noble region from

which many other Fijian tribes stemmed. As a mark of respect for that place,

other crew members whose forefathers came from Ra call him Matagali, meaning

having the same ancestral God, instead of using his given name. At every

anchorage, we as visitors (from other parts of Fiji and the world) must

present a "sevu -sevu" to the chief - a gift with which permission to stay

is sought. The gift is usually a "waqa", the root of the yagona plant which

produces the narcotic drink usually called kava. The presentation is solemn

and formalised. Chiefs lower their eyes and listen carefully to the deliberately

chosen words, the pitch, speed and rhythm of the speaker's trained voice

before clapping cupped hands to accept and welcome the newcomers.

Today,

Fiji sits on the main Pacific sea and air route and, thanks to sugar and

tourism, is, economically, the region's strongest and most developed nation.

Yet its people continue to value their heritage and traditions faithfully

in daily life. NAI'A's chef, Manasa, comes from Ra, a noble region from

which many other Fijian tribes stemmed. As a mark of respect for that place,

other crew members whose forefathers came from Ra call him Matagali, meaning

having the same ancestral God, instead of using his given name. At every

anchorage, we as visitors (from other parts of Fiji and the world) must

present a "sevu -sevu" to the chief - a gift with which permission to stay

is sought. The gift is usually a "waqa", the root of the yagona plant which

produces the narcotic drink usually called kava. The presentation is solemn

and formalised. Chiefs lower their eyes and listen carefully to the deliberately

chosen words, the pitch, speed and rhythm of the speaker's trained voice

before clapping cupped hands to accept and welcome the newcomers.  Kava

may well be the drug of this nation and others in the South Pacific, but

the ritual surrounding its use is most dignified. Fijians (mostly men)

gather daily in work, family or village groups to drink communally from

the kava bowl or "tanoa", discuss the day, debate local issues and sing.

Just listening to the artful weave of Fijian voices ringing out proud and

loud into a balmy tropical evening is a mind trip, let alone succumbing

to the gentle sedating effects of what is affectionately termed "grog".

Wherever you are in Fiji you'll hear the clanging sound of the dried pepper

root being crushed under a heavy steel pipe - it's like church bells bidding

the Lord's flock to prayer. The powder is then mixed with water and poured

into the tanoa before being passed in coconut shell cups to each of the

takers. Traditionally, the root was chewed up by women before being diluted

- a laborious method, but the chemical reaction that occurs during mastication

produces a far more potent mixture. All important occasions, including

welcoming guests, are marked with a formal kava ceremony. Fijians love

to watch foreigners wince over their first taste but enjoy it even more

if you chug a bowl empty without dribbling like an amateur and still manage

a satisfied grin afterwards. "Maca", the party will cheer as they cup their

hands and clap three times to show their appreciation. Experiencing and

following Fijian ceremony earns you respect and them pride.

Kava

may well be the drug of this nation and others in the South Pacific, but

the ritual surrounding its use is most dignified. Fijians (mostly men)

gather daily in work, family or village groups to drink communally from

the kava bowl or "tanoa", discuss the day, debate local issues and sing.

Just listening to the artful weave of Fijian voices ringing out proud and

loud into a balmy tropical evening is a mind trip, let alone succumbing

to the gentle sedating effects of what is affectionately termed "grog".

Wherever you are in Fiji you'll hear the clanging sound of the dried pepper

root being crushed under a heavy steel pipe - it's like church bells bidding

the Lord's flock to prayer. The powder is then mixed with water and poured

into the tanoa before being passed in coconut shell cups to each of the

takers. Traditionally, the root was chewed up by women before being diluted

- a laborious method, but the chemical reaction that occurs during mastication

produces a far more potent mixture. All important occasions, including

welcoming guests, are marked with a formal kava ceremony. Fijians love

to watch foreigners wince over their first taste but enjoy it even more

if you chug a bowl empty without dribbling like an amateur and still manage

a satisfied grin afterwards. "Maca", the party will cheer as they cup their

hands and clap three times to show their appreciation. Experiencing and

following Fijian ceremony earns you respect and them pride.

Tonga's

charm is its naiveté. The people and the natural environment seem

to be held up in time. And without major industry, save the recent butternut

pumpkin boom that bought many Tongans cars and VCRs, small-scale tourism

has become the biggest dollar earner. But as one resort owner boded, "If

you think things are slow in Fiji, just remember Tonga is about 30 years

behind!" The capital, Nuku'alofa, is the kind of place where you can lose

someone after lunch and be sure to bump into them before dark - they can't

go far. The Royal Palace is perched proudly on the waterfront right in

town. The crown prince is easily found lunching in the Nuku'alofa Club

and the police close off the main street behind the palace during the King's

regular bicycle riding sessions. In recent years he, Tui Taufa'ahou Tupou

IV, has personally led a major public fitness campaign to combat not only

his own obesity (he was 300 lbs) but also that of the great majority of

his subjects. His habit of wearing a motor bike helmet and ski goggles

when flying has earned him much attention during airport arrivals and departures.

Yet he commands absolute respect, displayed at street level by the wrap-around

woven matting, "ta'ovalas", Tongan's wear over their clothes. Don't be

surprised to see so much black clothing, as Tongans mourn the death of

(far extended) family members for many months! Don't be shocked to find

many transvestite Tongans, either. Called Fakaleiti, these men are dangerously

promiscuous in a country yet to suffer the effects of the AIDS virus. In

Polynesian custom, families without enough girls will raise a male child

as if he were female. He dresses as a girl and does girlsí chores as well

as dancing the female roles in the hypnotically beautiful traditional Tongan

dances. Upon reaching adulthood, many take their place as men in the community,

but not all.

Tonga's

charm is its naiveté. The people and the natural environment seem

to be held up in time. And without major industry, save the recent butternut

pumpkin boom that bought many Tongans cars and VCRs, small-scale tourism

has become the biggest dollar earner. But as one resort owner boded, "If

you think things are slow in Fiji, just remember Tonga is about 30 years

behind!" The capital, Nuku'alofa, is the kind of place where you can lose

someone after lunch and be sure to bump into them before dark - they can't

go far. The Royal Palace is perched proudly on the waterfront right in

town. The crown prince is easily found lunching in the Nuku'alofa Club

and the police close off the main street behind the palace during the King's

regular bicycle riding sessions. In recent years he, Tui Taufa'ahou Tupou

IV, has personally led a major public fitness campaign to combat not only

his own obesity (he was 300 lbs) but also that of the great majority of

his subjects. His habit of wearing a motor bike helmet and ski goggles

when flying has earned him much attention during airport arrivals and departures.

Yet he commands absolute respect, displayed at street level by the wrap-around

woven matting, "ta'ovalas", Tongan's wear over their clothes. Don't be

surprised to see so much black clothing, as Tongans mourn the death of

(far extended) family members for many months! Don't be shocked to find

many transvestite Tongans, either. Called Fakaleiti, these men are dangerously

promiscuous in a country yet to suffer the effects of the AIDS virus. In

Polynesian custom, families without enough girls will raise a male child

as if he were female. He dresses as a girl and does girlsí chores as well

as dancing the female roles in the hypnotically beautiful traditional Tongan

dances. Upon reaching adulthood, many take their place as men in the community,

but not all.

Fijians

fervently discuss politics (especially the two military coups of 1987)

while Tongans devotedly quote passages from the Bible. In Fiji, the struggle

for power is between the native islanders and Indians who came after colonisation

in the 1870s as indentured labourers to work the sugar cane fields and

now constitute half the population. In Tonga, the Wesleyan, Mormon and

Seventh Day Adventist churches challenge one another for devotees. A traditional

council of chiefs today advises and heavily influences a democratic parliament

in egalitarian Fiji. But in feudal Tonga, the King owns all the land and

"commoners" cannot ever rise to nobility. Recently, he was unrelenting

in his mission to stop his daughter marrying outside nobility.

Fijians

fervently discuss politics (especially the two military coups of 1987)

while Tongans devotedly quote passages from the Bible. In Fiji, the struggle

for power is between the native islanders and Indians who came after colonisation

in the 1870s as indentured labourers to work the sugar cane fields and

now constitute half the population. In Tonga, the Wesleyan, Mormon and

Seventh Day Adventist churches challenge one another for devotees. A traditional

council of chiefs today advises and heavily influences a democratic parliament

in egalitarian Fiji. But in feudal Tonga, the King owns all the land and

"commoners" cannot ever rise to nobility. Recently, he was unrelenting

in his mission to stop his daughter marrying outside nobility.

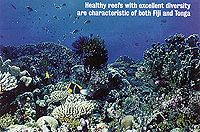

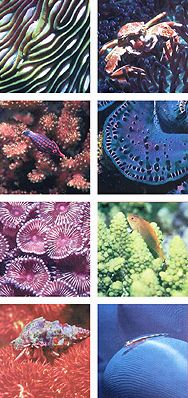

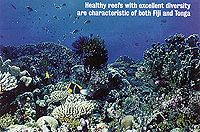

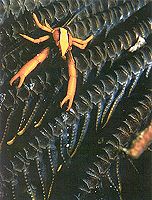

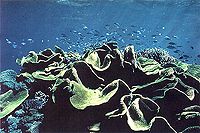

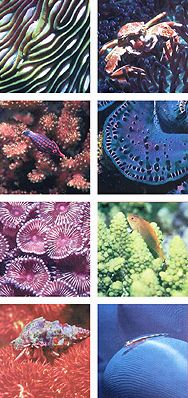

Fiji and Tonga are close geographically

but in many ways they are realms apart underwater. To the navigator they

are the world's most treacherous mazes, but to divers and biologists, both

places are a heavenly array of growing coral reefs. Fringing and barrier

reefs occur throughout the region but while Fiji is famed for it's luxuriant

soft corals and vibrant fish life, Tonga's main attractions are clear turquoise

water, mostly unexplored, and the lonely Antarctic humpback whale tribe

that mate and calve here. Lonely in that they were hunted more heavily

and more recently than the planet's other tribes. And lonely in that their

total population numbers only a few hundred and their future remains tentative.

NAI'A's live-aboard diving expeditions link Fiji and Tonga. The ship takes

divers to Fiji's most remote, rich and exciting reefs for most of the year.

In Winter (July/August) she doubles as a scientific research and passenger

vessel to find, observe, identify and record humpback whales around Tonga's

Hapa'ai Group of islands.

The diving scene in Fiji is well-organised

and extremely varied. Almost every resort offers SCUBA services and there

are many specialist diving operators on the main islands and smaller offshore

destinations as well as a few top-class live-aboard dive boats. The western

side is characteristically warm and sunny with clear and fairly shallow

sites easily accessible from day boats crewed often by experienced and

competent local guides, divemasters and instructors. Beqa Lagoon, Vatulele

and Kadavu Island in the south of the main island Viti Levu are well-known

for their lush coral bommies and equally lush rainforested islands. The

south-eastern side of Vanua Levu and around the garden island of Taveuni

boasts excellent soft coral diving, especially along the current fed barrier

reefs and channels. But, as with almost all destinations, the further afield

you go, the better the diving. And the only way to experience the magnificent

variety of terrains and conditions Fiji has to offer is to live at sea

and change your location every day. NAI'A was designed precisely

for that purpose - to reach the finest places in complete comfort. NAI'A's

usual itinerary takes in several reefs and islands that, by no accident,

lie in a row along a wide deep channel of water between Viti and Vanua

Levu through which the prevailing south-east trade winds boost the flushing

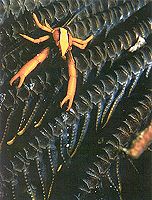

of nutrients and clean ocean water. Out here the reefs support not only

spectacular soft coral growth teeming with tiny bright reef fish, but also

rarely seen nudibranchs, shells, shrimps and anemones and bizarre creatures

such as such as harlequin and hairy ghost pipefish, deep-water blue ribbon

eels and decorated dartfish. In lagoon passages wild currents carry clean

sea and schooling predators - barracuda, big-eye jack, snapper, mackerel

and sharks. At the islands of Gau, a resident group of grey reef sharks

cruise among divers while hammerheads and manta rays are usually spotted,

sometimes staying close and offering divers their most breathtaking experiences.

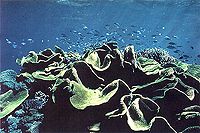

In contrast, Tonga's coral reefs are quieter

- as is the local diving industry. Yet, Tonga was the first South Pacific

nation to set aside marine reserves. Two of the 10 sites where collecting

and some fishing is prohibited are giant clam farms. The half a dozen land-based

scuba diving operators are located around the main island of Tongatapu

and in the northern Vava'u group. Only a fraction of the country's 170

islands and many more submerged reefs have been explored - fewer than 40

islands are inhabited! The Niua and Ha'apai Groups are truly frontier territory

making virtually every dive exploratory. Most of the islands are low coral

atolls, although there are several active volcanic islands and the main

landmasses boast extremely fertile soil. Ha'apai's Kau Island is a volcanic

cone reaching 1109m out of the sea and the neighbouring Tofua, the site

of the Bounty mutiny, is an active, spewing volcano. Tonga is experiencing

the earth's fastest shift at 10 cm in the direction of Samoa each year!

Vava'u is an idyllic vision of brilliant blue water surrounding shallow

fringing reefs and high island peaks. Some dramatic coastal caves below

the surface harbour white tip sharks, lobster and schooling fish - others

form interesting dive sites by their shape alone. Mariner's Cave at Nuapapu,

a giant bubble cave that materialises about 10 feet under and tunnelling

20 feet into a submerged ledge of coral, is a fascinating diversion - especially

if you believe the romantic tale of a love-struck young chief who captured

and hid his princess inside the cave to save her from execution by the

tyrant king, winning her heart in the process. Other unique sites in Vava'u

include Gorgonia Valley which is exactly what the name implies - layer

upon layer of giant sea fans growing upright from an undersea gully. Before

you leave the stunning fjord-like harbour, Port of Refuge, at Neiafu, visit

the Clan McWilliam wreck - a 300 foot long copra trader that caught

fire and never made it to port. The astounding visibility (in winter 150ft

is not uncommon) may mean the concentration of life on the reef is less

than in Fiji. But the view it opens up of the rising and falling seascape,

sweeping detail of hard coral gardens, towering pinnacles and gaping tempting

caverns is a spectacular alternative.

The exhilaration of witnessing the power

of a breaching humpback whale and the grace of it gently gliding inches

from its kin is the reason many lovers of the sea are beginning to travel

to tiny Tonga. The tribe of humpbacks that mate and calve here migrate

from their feeding grounds in Antarctica, along the New Zealand coast,

arriving from July and staying until September/October. The Tonga tribe

are even more special than other groups of humpbacks as they number so

few and are understood so little. Until commercial whaling - and more recently

large-scale illegal whaling from Soviet ships - devastated the species

so effectively, southern ocean humpbacks wintered in Fiji and were seen

in groups as late as the 1960s. Hunted until 1979 for their oil, meat and

bone, scientists now pursue them for knowledge - theirs and ours. While

ordinary folk vie for a few precious shared moments with these giants in

their own giant realm. NAI'A's expeditions to Tonga run as passenger supported

humpback whale research trips with the opportunity to scuba dive also.

The aim is to learn about and enjoy the whales as they seek warmth

and shelter among these splendid tropical islands and reefs - in much the

same way we do.

For sports fans, the Rugby match was a

close one. Tonga won the game but Fiji took home the tournament trophy

with top points overall. War was averted. Sunday is the Sabbath after all.

A FATAL SHORE

Early Fijians gave names to every one of their

more than 350 islands, reefs and banks - a feat that speaks volumes about

their skill at sea and their affinity with this aquatic environment. For

centuries, islanders have held with pride diving and fishing skills that

have guaranteed the health and success of their families and village communities.

But a sorry diving epidemic is gathering momentum in Fiji and other South

Pacific island nations where a need for cash is injuring and killing hard-working

young men whose only crime is ignorance.

Beche de mer, or sea cucumber is a much

sought after delicacy throughout South East Asia. Stocks of the animal

have been severely depleted in Asia's waters, but still occur in abundance

on the reefs of South Pacific islands such as Fiji. Beche de mer traders

travel to Fijian villages asking local fishermen to harvest the animals

in return for payment for the amount they can gather. Traders bring with

them diving equipment, usually compressors and hookah gear, and sometimes

a boat that enables the divers to reach deeper waters, stay for longer

periods of time, collect greater numbers of beche de mer and earn more

money than they ever could by simply free diving. The gift may seem a generous

and business-wise gesture but it comes with a hidden high price. What these

traders fail to give is training to cope with the rigours of breathing

compressed air, education about the effects of nitrogen and the need for

decompression and tools to maintain the equipment safely. Without depth

gauges and timers, diver have no idea how long they stay down or how deep

they go. A common yet terrifying dive profile reads, "hose length more

than 100 feet, bottom time about two hours". The result: Fiji's hyperbaric

chamber is in almost constant use treating sick beche de mer divers.

But it doesn't always work. The villagers,

if they recognise their ailments to be diving related, often need to travel

long distances to the chamber, journeys that can take several days. In

Fiji, the use of compressors for diving is illegal. Often sick divers will

avoid seeking help for fear of alerting authorities to the village industry

that is otherwise lucrative. Many young men are dying - some despite treatment,

some before they reach doctors and some before they even reach the surface.

Many more are permanently incapacitated, perhaps suffering mysterious flu-like

symptoms, perhaps paralysed, but no longer able to work proudly and provide

for their families.

The really frightening fact is that untrained

beche de mer divers are being treated in Fiji just because they can be.

The issue is at least being addressed there. Fiji has a well-organised

diving industry, a relatively aware government, good nationwide communication

and a recompression chamber. What of the more remote islands where seeking

any medical help, let alone hyperbaric treatment, is out of the question?

Out there, fatigue, injury, paralysis and death are just daily risks in

a modern world where money, not health, means survival.

The Last Lonely Tribe

I was mugged in Tonga - a wonderful experience

that I will treasure for the rest of my life.

She weighed about 30 tonnes and stretched

as many feet long in front of us - escape was not an option. She was so

close, the roaring gusts of her breath sent a spray of wet sticky mucous

into our faces. She was no monstrous pirate though, simply a curious and

playful humpback whale. Neither were we victims. Mere humans, so struck

with awe we must have seemed to her more like over-excited children or

lunatics set adrift at sea. Circling NAI'A closely, spyhopping at the bow

and taunting the swimmers into deeper water, she trapped the ship, the

captains unable to move or manoeuvre in any direction for fear of injuring

the immense mammal. In Hawaii, humpback whale watchers call this "mugging".

She stayed with NAI'A for several hours, tumbling and turning and eyeing-off

we lunatics - splashing and diving and squealing with glee through our

snorkels. This whale fulfilled many people's dreams that day. What she

felt about us we'll probably never know. There's no doubt though, that

she sought our attention, as much as we had hoped for hers.

We came aboard NAI'A to Tonga's remote

Ha'apai island group to find humpback whales (Megaptera novaeanglidae)

, to gather photographs identifying individuals, to record their song,

to observe their behaviour in breeding and calving grounds and to know

that even this most endangered tribe of Antarctic humpbacks - so diminished

by hunters and criminals - is holding on. Despite enormous public opposition

worldwide, a new era in commercial whaling looms ominously close. We carried

with us working scientists and volunteer assistants from Auckland University

where a long-term study of the Tonga tribe was begun in earnest three years

ago. We came also for the journey of a lifetime - a luxury live-aboard

cruise among truly untouched atolls and dives on genuinely unexplored coral

reefs. And we came maybe, just maybe, for the chance to swim alongside

an inimitable humpback whale.

We got everything we hoped for and more!

Every day we spotted whales, sometimes many more than was possible to keep

track of. We saw mothers with new born calves wildly breaching and tail

slapping then peacefully nursing and resting - the calves offered up to

the surface air on their mothersí rostrum like a gift lifted to God. We

saw charging pods of males battling violently for dominance and putting

to rest the old cliché about these animals being "gentle giants".

We saw some pairs and many lone whales, some singing probably to impress

and seduce a nearby mate, some wandering aimlessly over shoals and others

clearly with a destination and a deadline. Sometimes the whales continued

without paying us any mind, sometimes they chose to avoid us and a sometimes

they surfaced right next to NAI'A, first checking out the vessel and the

vibrating hum of its engine, then allowing the game and ready to slowly

slip into the same sea and swim together in endless blue. Each night still

I fall asleep with the image of two humpback whales gliding synchronously

beneath me into shafts of converging sunlight, using only their massive

pectoral fins to steer, then rolling over in slow-motion with a mutual

sweep of those "wings" exposing brilliant white bellies and bulbous probing

eyes staring right at me.

I've told myself over and over that to

learn the truth about how these animals live, I can't afford to romanticise

them or see something mythical and magical in every simple move they make.

But it's impossible not to hoot and yell at the sight of a 40 tonne whale

lifting its entire body clear of the water and crashing down again with

a thunderous splash that lasts almost a minute. I'm only human after all.

The humpback whale is a creature of astounding size, grace and character

- not to mention environmental significance. But our luck in finding them

does not answer the real question: In a tribe so few in number and so sparsely

scattered, how do they find each other?

On our way back to Fiji, more than 50 miles

out into open sea and far from where these whales are "supposed" to be,

a single humpback lay still on the surface, facing the sunset as we were

and bobbing underneath only briefly when NAI'A passed just 50 yards away.

The sight of this lonely whale, perhaps even lost, reduced me to tears.

Our empathy for whales, I believe, matches the understanding we lack. Perhaps

the humpback whale's desperate search for a mate and tentative grip on

survival illuminates our own solitary nature and our own mortality. Perhaps

humankind is the lonely one - craving the company of something grander,

more intelligent and sensitive than ourselves.

Late one afternoon, NAI'A was anchored

off a stunning island. Villagers were fishing from dugout canoes, scuba

divers were being ferried back and forth to a nearby reef, scientists scanned

the surrounding water for whale song, vacationers read novels in the fading

sunlight while the aroma of an almost ready dinner wafted onto the deck.

About 200 yards off NAI'A's starboard side, a humpback mother and newborn

calf - the same pair we had followed carefully and observed since midday

and one of three mother and calf pairs we had watched that day - remained

milling unaffected by our presence. This, for me, was as thrilling as any

close encounter. To see whales without having to search. To watch them

from a modest distance doing whatever comes naturally, unconcerned by our

separate activities. To know these are not the last humpback whales we'll

ever see in Tonga. This is the way it should be.

NAI'A

Home Page

Rugby

and religion reign supreme down here. At least, that's in the places where

following football is not officially classed as worship already. I'm talking

about the much romanticised South Pacific islands of Fiji and Tonga and

Rugby is the particular brand of football played so proudly in these parts.

This is a where every home in even the most remote villages displays a

poster of the local "footie legend", Jonah Lomu, the way a picture of the

Queen of England once adorned every mantelpiece in the colonies. The Pope?

Well, he rarely rates a mention nowadays.

Rugby

and religion reign supreme down here. At least, that's in the places where

following football is not officially classed as worship already. I'm talking

about the much romanticised South Pacific islands of Fiji and Tonga and

Rugby is the particular brand of football played so proudly in these parts.

This is a where every home in even the most remote villages displays a

poster of the local "footie legend", Jonah Lomu, the way a picture of the

Queen of England once adorned every mantelpiece in the colonies. The Pope?

Well, he rarely rates a mention nowadays.

Tonga's

charm is its naiveté. The people and the natural environment seem

to be held up in time. And without major industry, save the recent butternut

pumpkin boom that bought many Tongans cars and VCRs, small-scale tourism

has become the biggest dollar earner. But as one resort owner boded, "If

you think things are slow in Fiji, just remember Tonga is about 30 years

behind!" The capital, Nuku'alofa, is the kind of place where you can lose

someone after lunch and be sure to bump into them before dark - they can't

go far. The Royal Palace is perched proudly on the waterfront right in

town. The crown prince is easily found lunching in the Nuku'alofa Club

and the police close off the main street behind the palace during the King's

regular bicycle riding sessions. In recent years he, Tui Taufa'ahou Tupou

IV, has personally led a major public fitness campaign to combat not only

his own obesity (he was 300 lbs) but also that of the great majority of

his subjects. His habit of wearing a motor bike helmet and ski goggles

when flying has earned him much attention during airport arrivals and departures.

Yet he commands absolute respect, displayed at street level by the wrap-around

woven matting, "ta'ovalas", Tongan's wear over their clothes. Don't be

surprised to see so much black clothing, as Tongans mourn the death of

(far extended) family members for many months! Don't be shocked to find

many transvestite Tongans, either. Called Fakaleiti, these men are dangerously

promiscuous in a country yet to suffer the effects of the AIDS virus. In

Polynesian custom, families without enough girls will raise a male child

as if he were female. He dresses as a girl and does girlsí chores as well

as dancing the female roles in the hypnotically beautiful traditional Tongan

dances. Upon reaching adulthood, many take their place as men in the community,

but not all.

Tonga's

charm is its naiveté. The people and the natural environment seem

to be held up in time. And without major industry, save the recent butternut

pumpkin boom that bought many Tongans cars and VCRs, small-scale tourism

has become the biggest dollar earner. But as one resort owner boded, "If

you think things are slow in Fiji, just remember Tonga is about 30 years

behind!" The capital, Nuku'alofa, is the kind of place where you can lose

someone after lunch and be sure to bump into them before dark - they can't

go far. The Royal Palace is perched proudly on the waterfront right in

town. The crown prince is easily found lunching in the Nuku'alofa Club

and the police close off the main street behind the palace during the King's

regular bicycle riding sessions. In recent years he, Tui Taufa'ahou Tupou

IV, has personally led a major public fitness campaign to combat not only

his own obesity (he was 300 lbs) but also that of the great majority of

his subjects. His habit of wearing a motor bike helmet and ski goggles

when flying has earned him much attention during airport arrivals and departures.

Yet he commands absolute respect, displayed at street level by the wrap-around

woven matting, "ta'ovalas", Tongan's wear over their clothes. Don't be

surprised to see so much black clothing, as Tongans mourn the death of

(far extended) family members for many months! Don't be shocked to find

many transvestite Tongans, either. Called Fakaleiti, these men are dangerously

promiscuous in a country yet to suffer the effects of the AIDS virus. In

Polynesian custom, families without enough girls will raise a male child

as if he were female. He dresses as a girl and does girlsí chores as well

as dancing the female roles in the hypnotically beautiful traditional Tongan

dances. Upon reaching adulthood, many take their place as men in the community,

but not all.

Fijians

fervently discuss politics (especially the two military coups of 1987)

while Tongans devotedly quote passages from the Bible. In Fiji, the struggle

for power is between the native islanders and Indians who came after colonisation

in the 1870s as indentured labourers to work the sugar cane fields and

now constitute half the population. In Tonga, the Wesleyan, Mormon and

Seventh Day Adventist churches challenge one another for devotees. A traditional

council of chiefs today advises and heavily influences a democratic parliament

in egalitarian Fiji. But in feudal Tonga, the King owns all the land and

"commoners" cannot ever rise to nobility. Recently, he was unrelenting

in his mission to stop his daughter marrying outside nobility.

Fijians

fervently discuss politics (especially the two military coups of 1987)

while Tongans devotedly quote passages from the Bible. In Fiji, the struggle

for power is between the native islanders and Indians who came after colonisation

in the 1870s as indentured labourers to work the sugar cane fields and

now constitute half the population. In Tonga, the Wesleyan, Mormon and

Seventh Day Adventist churches challenge one another for devotees. A traditional

council of chiefs today advises and heavily influences a democratic parliament

in egalitarian Fiji. But in feudal Tonga, the King owns all the land and

"commoners" cannot ever rise to nobility. Recently, he was unrelenting

in his mission to stop his daughter marrying outside nobility.